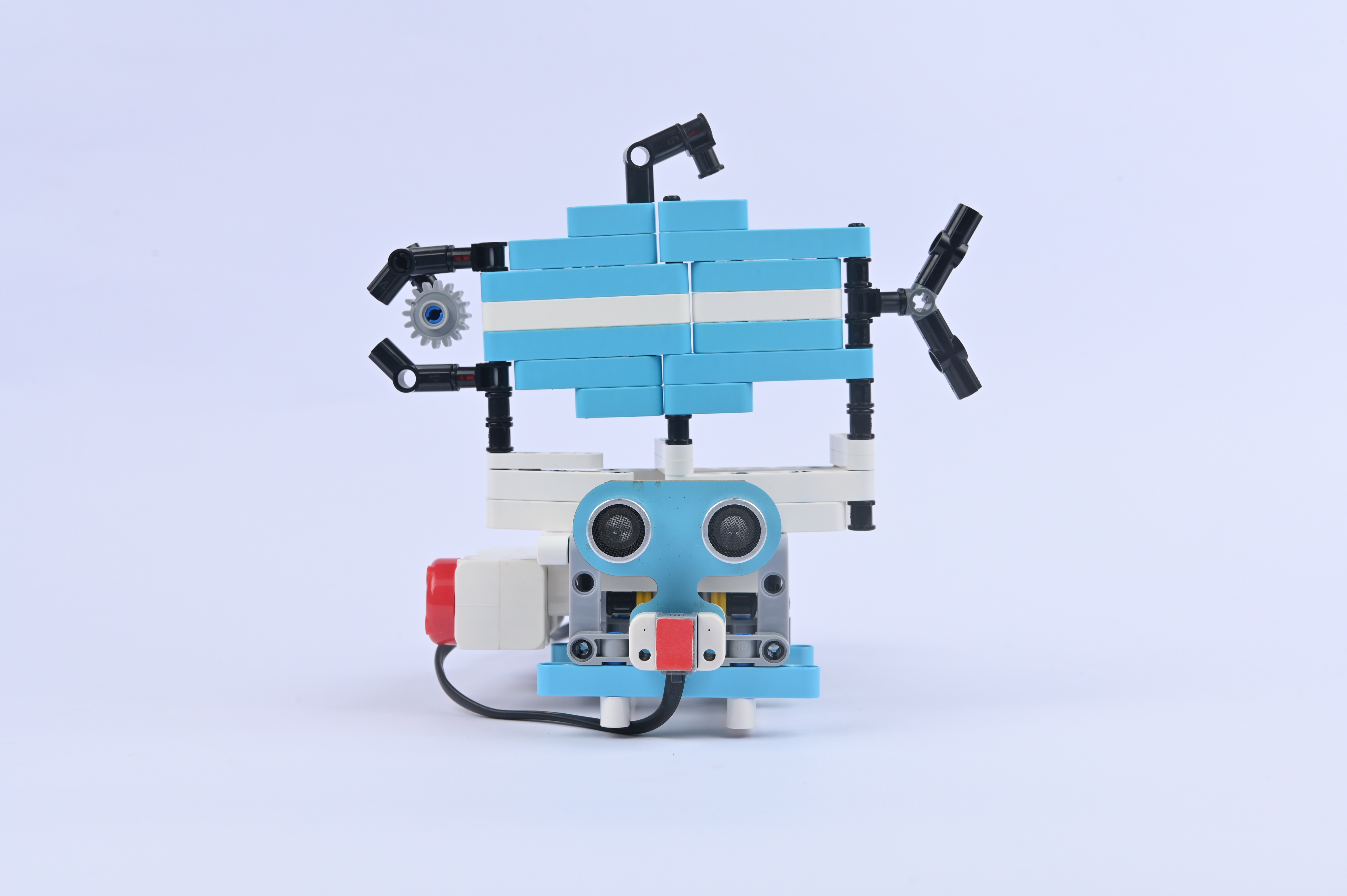

One night, with the help of his friends on the island, Ian successfully landed on the island. Ian has been on the island for two days and made a new friend, Jack. On this day, Jack excitedly told him that the island was holding a Harvest Festival with many interesting activities, and he dragged him to participate in the building block model construction competition. The two hurried to the scene and heard the host announce: "This year's theme is building fish models, and we'll see whose model is the most lifelike. Come and join this joyful building block construction competition with Ian and Jack!